|

No. 8, High Street

|

|

|

In its original form the building comprised a large double-jettied two storey structure set `end-on' to the street. The second floor was divided into five bays and was almost certainly covered by a crown-post roof. Large sections of the building had already been lost prior to its recent disaster. Many of the buildings on this side of the High Street were destroyed by a great fire on August 18th, 1865. Fortunately this property escaped the worst of the damage, though its roof, which was badly burned, had to be replaced. Considerable alterations were undertaken in the eighteenth century resulting in the loss of the original facade and much of the internal framing, nineteenth-century brickwork now replaces virtually all the framing along the south-east elevation. One of the most unusual features of this building is the use of double tie-beams at eaves level. The upper cambered tie-beam is framed into the roof structure in the usual manner. Rather surprisingly a second uncambered tie-beam is located immediately below. This additional beam supported a contemporary attic floor, of which only the joists in the rear bay now survive. This building was clearly built at a transitional time in the development of vernacular timber-framed houses. The crown-post roof is clearly a late example of its type, constructed when side-purlin structures were first being introduced. Despite the continuation of an established roof style. it seems that garret accommodation, a more progressive idea, was included in the original design. In this respect the building is ahead of many of its contemporaries. These two features, which are not wholly compatible and rarely seen together, require the rather unusual double tie-beam assembly, just discussed, to support the floor frame. It seems likely that the roof originally terminated in a jettied gable over both front and rear elevations. No framing survives along the street frontage, however the arrangement probably matched that of the rear elevation where some evidence still exists. Here it is suggested that the attic joists oversailed the rear eaves plates, in a similar fashion to the jettied floors below, to support a gable end. The relative level of the lower tie-beam and the eaves would facilitate this arrangement. The north-west elevation, which is the most complete, contains several interesting features. Of these the use of brick infill is the most surprising. In most cases each panel, the space between the principal posts, is divided by three studs and crossed by a substantial tension brace. Small buff bricks, which can only be contemporary with the framing, infill the areas between the timber. The wide spacing between the studs is certainly not designed to support lathes and daub. Additional mortices for further lightweight studs, necessary for lathes, are not present. An offset to the recessed sides of the northernmost post provides for the thickness of the brickwork. These details confirm that the framing was constructed to support a brick infill. This brickwork represents some of the earliest discovered in vernacular use in Canterbury. Although brickwork occupies practically all the panels, several areas are infilled with the more traditional lathe and daub. This is applied to large, closely spaced studs in the usual manner. There is no obvious explanation for this inconsistency, and it was not clear whether this replaced areas of failed brickwork. Only the central bay of this elevation incorporated fenestration. A shutter groove, observed above windows elsewhere in the building, is not present here. Small square holes, probably left by forged metal gudgeon pins, suggest that internal hinged shutters were used to secure these windows. Several scarfs, of the splayed and tabled variety with under-squinted butts, were observed in the building. These suggest an earlier date for the building than is perhaps indicated by some of the other features. A rough stone dwarf wall, comprising a mixture of chalk, Caen and flint, still survives beneath this elevation. Several areas have been repaired in later red brick, presumably of nineteenth-century date. An early cellar, of possible thirteenth-century date, still survives beneath the later building, now forming part of a larger basement. The best area of facing, which comprises a mixture of chalk, Caen and flint, survives along the north-west elevation. A small niche, with Caen jambs and small pointed arch, together with sizeable areas of ashlar are also visible along this wall. Clearly an earlier building occupied this site before the construction of what survives today. Despite severe fire damage and previous losses enough of the rear elevation survives to reconstruct its original form on paper. The arrangement of centrally located fenestration, subsequently enlarged to take inserted eighteenth-century sash windows, can be observed at first floor level. Rebates on the jambs and centre post indicate that window-heads, presumably decorated arches, once embellished the openings. The squinted housings for the sills, which were face pegged rather than tenoned to the uprights, are visible on the sides of these posts. A groove to take horizontally sliding shutters is still visible above the openings. Two very low curving braces, similar to those on several other buildings in Canterbury, survive below this fenestration, and arch-braces cross the outer panels from above. Unfortunately only the lower plate and a fragment of eaves plate survives at second floor level. The details observed on these two timbers are consistent with those recorded below. It seems reasonable to assume that the arrangement was similar. Only the jetty plate and corner posts survive at ground floor level, where the former jetty has been underbuilt in modern fabric. Access to the rear of the property was provided by a doorway located in this elevation. A wide rebate, which runs up the easternmost corner post and across the soffit of the jetty plate (which must have continued down the missing door post), once housed a large carved wooden door-head positioned above this entrance. Two more door-frames were uncovered on this side of the building, incorporated into the ground floor partitions at each bay division. These openings were framed with small arch-braces (similar to jetty brackets), providing an opening similar in shape to that of the rear door. It is clear from the positions of these door-frames that a side passage ran from the street frontage through to the rear of the building.

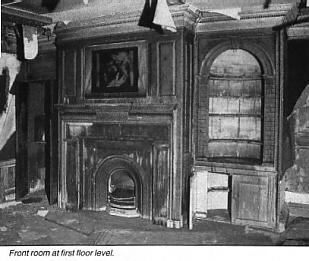

The size and weight of the framing, in particular the substantial floor joists, together with the crown-post roof and splayed scarfing all suggest an early to mid fifteenth-century date, but the low tension bracing and particularly the brick infill suggest a sixteenth-century date. Considering these points, a construction date in the last quarter of the fifteenth century seems reasonable, with the brickwork representing some of the earliest found in Canterbury. It will come as no surprise to learn that since its conception the primary structure has undergone many phases of alteration and addition. These periods of refurbishment have introduced numerous fixtures and fittings to the interior of the property. The first major upgrading of the property appears to have occurred in the seventeenth century. A fine Jacobean fireplace, probably of mid seventeenth-century date, originally occupied the rear room at first floor level. Unfortunately very little of this survives. The overmantel and much of the lower surround was unfortunately destroyed by the recent fire. Its lavishly decorated pilasters, capped by classical capitals and decorated frieze were typical of the period. A Victorian cast iron grate has been inserted into the former hearth. Another interesting feature is the early balustrade detail around the staircase at first floor level. The turned balusters, which are short and stout, possibly date from the mid seventeenth century though these could be later. Numerous sections of plain seventeenth-century panelling survive throughout the building, in particular around the landing walls up to dado height. This type of panelling is very common, and has been observed in numerous properties throughout the locality. The vertical stiles and muntin pieces are typically scratch moulded whilst the horizontal rails are simply chamfered along their upper arris. Another large area survives in the central room at first floor level with a few smaller fragments surviving on the ground and second floors. It is always difficult to ascertain whether panelling of this type survives in situ or whether it has been re-used from another room or perhaps another building. There is a tendency for it to looked patched together and cut to fit, even when it is clearly an original feature. This is perhaps because it was fabricated in bulk by an outside supplier to a standard size. Once purchased it would be trimmed and modified to fit the room being refurbished. A small cupboard door, similar in pattern to the panelling just discussed, is located over the stairwell at second floor level. It is secured by `H'-type hinges with shaped ends, some of the most common internal door hinges used throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The door has obviously been cut down and reused. The next major period of refurbishment seems to have occurred in the late Georgian period. Virtually all the features in the front room at second floor level appear to date from the third quarter of the eighteenth century. A large fireplace, with panelled pilasters and frieze, forms the centre piece along the south-east wall. The panelled overmantel still survives above the heavily moulded mantel shelf. A grate of mid to late nineteenth century now occupies the former hearth. A shelved niche with smi-circular opening and dropped keystone is located adjacent to the fireplace. Its pillars, decorated with imitation block-work, rise from an integral cupboard below. A heavily moulded cornice with applied dentilations, surprisingly made from a sequence of smaller wooden elements rather than plaster, runs contiguously around the room Below this was a picture-rail, chair-rail and finally a deeply moulded skirting. It seems that the rear room at first floor level was also refurbished at around this time. Only the skirting, chair-rail and fragments of picture-rail have survived the fire. These mouldings, which are shallower and less complex than those in the front room, could suggest a slightly later date for this room. The earlier medieval fenestration was replaced at this time with larger sash windows which have unfortunately been destroyed. Several more features can be attributed to this period. In particular, the hall archway at second floor level. This semicircular arch with plain soffit and dropped key-block springs from a moulded architrave. The glazed doors, hung to the rear face of the arch, appear to be contemporary. A lightwell, also located in the second floor hall, is enclosed by turned balusters and a heavy moulded handrail. A final phase of Georgian refurbishment occurs at the very end of the eighteenth if not the early nineteenth century. This can be seen in the front room at second floor level which, although split in two by a later Victorian partition, retains most of its fittings. The most interesting feature is undoubtedly the fireplace. The cast-iron grate incorporates engaged columns complete with locking bands and corner roundels of floral design. The architectural elements can certainly be attributed to the Gothic revival of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. This is consistent with an early photograph of the facade which shows fenestration of Gothic influence. Door architrave, chair-rail and skirting mouldings (no cornice), considerably less elaborate than those previously discussed, survive intact. A wooden fire surround, with fluted corner blocks, has a similar but reversed moulding to the chair-rail, suggesting a contemporary date. The alterations and additions undertaken by the Victorians have fortunately been limited to a few sash windows, door frames and cupboards. These are of little interest. We are fortunate that the effects of this century have been limited to the ground floor, until recently Dewhurst the Butchers. No. 8 High Street, which survives as an interesting and sizeable example of a late medieval building, has revealed several important and unusual features. In particular, the early brick infill and double tie-beam roof. The opportunity to survey this structure has provided a valuable addition to our growing knowledge of Canterbury's vernacular architecture. Evidence of an earlier preceding stone structure, not affected by the recent repair works , suggests an area for future investigation. This property, in common with most of Canterbury's historic buildings, has undergone many alterations and additions throughout the centuries. Numerous seventeenth-century fittings together with three well-preserved Georgian rooms add considerably to the interest and historical value of the building.

|

Peter Collinson Last change: 18th November 2018

The early fabric contained within the property was first discovered

by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust in 1978 during repair works to

the shop front. The oak joists and timbers revealed behind the plain

nineteenth-century facade and low pitched slate roof of this building

clearly belonged to a medieval building. Unfortunately, most of the

historic material remained hidden, and it was only possible to record

small elements of what was originally a very substantial structure. The

opportunity for further recording work regrettably came only as the

result of a disastrous fire in the summer of 1992. Much of the building

was seriously damaged, though nearly all the surviving timber frame was

uncovered as a result of the fire and subsequent repair work. Not

surprisingly a considerable amount of this material was severely burnt

and damaged, making its analysis extremely difficult.

The early fabric contained within the property was first discovered

by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust in 1978 during repair works to

the shop front. The oak joists and timbers revealed behind the plain

nineteenth-century facade and low pitched slate roof of this building

clearly belonged to a medieval building. Unfortunately, most of the

historic material remained hidden, and it was only possible to record

small elements of what was originally a very substantial structure. The

opportunity for further recording work regrettably came only as the

result of a disastrous fire in the summer of 1992. Much of the building

was seriously damaged, though nearly all the surviving timber frame was

uncovered as a result of the fire and subsequent repair work. Not

surprisingly a considerable amount of this material was severely burnt

and damaged, making its analysis extremely difficult.

In general the construction of this building, which has obviously

been thrown together in a quick and functional manner, without recourse

to unnecessary decoration or detail, is solid and substantial. In

several respects however the structure, which incorporates some re-used

timber, is a little haphazard and inconsistent, for example the

arrangement of principal posts and tie-beams (which don't always

coincide as they should) or the use of brick or daub infill. For this

reason, together with a considerable quantity of missing or damaged

timber, interpretation has proved difficult if not impossible in some

areas.

In general the construction of this building, which has obviously

been thrown together in a quick and functional manner, without recourse

to unnecessary decoration or detail, is solid and substantial. In

several respects however the structure, which incorporates some re-used

timber, is a little haphazard and inconsistent, for example the

arrangement of principal posts and tie-beams (which don't always

coincide as they should) or the use of brick or daub infill. For this

reason, together with a considerable quantity of missing or damaged

timber, interpretation has proved difficult if not impossible in some

areas.