|

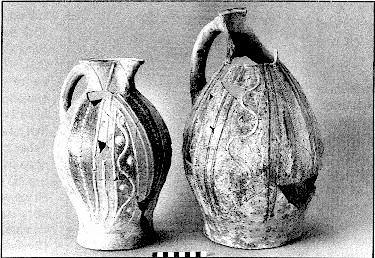

Two Medieval London-type jugs from Longmarket

|

|

|

Two of the most significant medieval pots found on the Longmarket site are the subject of this note. Both are of considerable interest and beauty and although broken they are remarkable for their state of completeness and preservation. The reason for their excellent condition is that both vessels were thrown to the bottom of two separate cess-pits or latrines where they lay undisturbed for the next seven centuries.  Both are glazed wheel-thrown jugs in what is known as London-type ware. The kilns for this `type' have never been discovered but there is little doubt that it was made somewhere in the London area, at a time when London potters were heavily influenced by French pottery styles. They have a fine sandy fabric, dull orange in colour with a pale grey core. A creamy white slip or liquid clay has been smeared all over the outside of both vessels including the handles and spout and partly inside the neck, but it stops a few centimetres above the base where it was deliberately cleaned away with a knife or perhaps a cloth or leather pad. The smaller of the two (on the left in the photo) is a baluster jug decorated in the Rouen style and dates to c. 1200-1250 A.D. This style consists of contrasting creamy white and dark red painted zones defined by applied strips in white clay with further details, such as studs and pellets, also executed in white clay (the excavators christened it the `rhubarb pot' due to this rhubarb- and-custard colour scheme). This is a variation of the chevron design which was popular both on London and Rouen (Normandy) jugs. On some jugs, such as this one, the design seems to echo motifs found in Norman architecture and perhaps also the wrought ironwork seen, for example, on church doors (hence the `studs' and `nails'). The handle has been plugged-in through the body wall in typical London fashion while a separate bridge spout has been applied to the front of the jug. A clear pitted glaze covers most of the upper two thirds of the body but the neck is only partially glazed while the handle and adjacent area are glaze-free. Glaze dribbles on the underside suggest that like most London jugs this example was fired upside-down. The second vessel (on the right in the photo) is a large rounded jug decorated in the North French style. This was more long-lived than the Rouen style being present on London excavations as early as c. 1200 and possibly still in circulation as late as c. 1340, albeit on a much reduced scale. Other imported and local wares found in the same cess-pit suggest however that this particular jug was discarded around 1275-1300 A.D. On this jug the plain paired vertical strips are of applied red-brown body clay which contrasts with the overall white slip background. The sinuous strips with their intervening smeared scales and the vertical diamond-rouletted strips are all in applied white clay. Like the Rouen-style jug glaze coverage is confined to the upper two thirds of the body and avoids the handle area. The glaze itself is pitted and mottled green; its uneven and patchy application over a background of contrasting red and white, plain and decorated details, gives the vessel a typical medieval exuberance which many people find charming, even beautiful, but which others find garish or repulsive. As with the first jug the handle on this one has also been plugged-in, it is also slightly facetted and at the top are two `ears' of applied clay - a typical North French feature. The spout is unfortunately missing but probably resembled that of the first jug. Under the base there are some large glaze splashes with a contact scar from the rim of a similar jug stacked upon it in the kiln, both, as usual, fired upside down. The wood-lined cess-pit which produced the Rouen-style jug lay in the back yard of a property owned around 1200 by a certain William Malemie, about whom nothing further is known. One is naturally tempted to associate the jug with William and certainly the dating does not preclude this, particularly if he lived for some years after 1200. There is some archaeological evidence however that William Malemie's back yard may have been encroached upon by his influential neighbour Terric the Goldsmith, or Terric's sons, early in the thirteenth century, but eventually the original Malemie boundary was re-established. Probably we will never know for certain to whom the jug belonged but in archaeological terms it is still quite an achievement to narrow it down to just one or two known families. Both the Malemie and Terric families undoubtedly belonged to Canterbury's wealthy artisan or merchant class, a fact reflected in their choice of quality French-style tablewares from London in preference to the less sophisticated wares of the Tyler Hill kilns located just outside Canterbury. The same is true for the unknown owner of the slightly later North French-style London jug. His stone-lined cess-tank yielded jugs from Tyler Hill, London, and some particularly fine whiteware jugs from the Saintonge area of south-west France. Neither of the Longmarket jugs is exactly paralleled in the published corpus of jugs in London-type ware, the forms and many of the decorative elements are, but the precise combinations as seen here appear to be entirely new. They are thus an important addition to the study of this ware as well as the study of medieval pottery as a whole.

|

Peter Collinson Last change: 18th November 2018